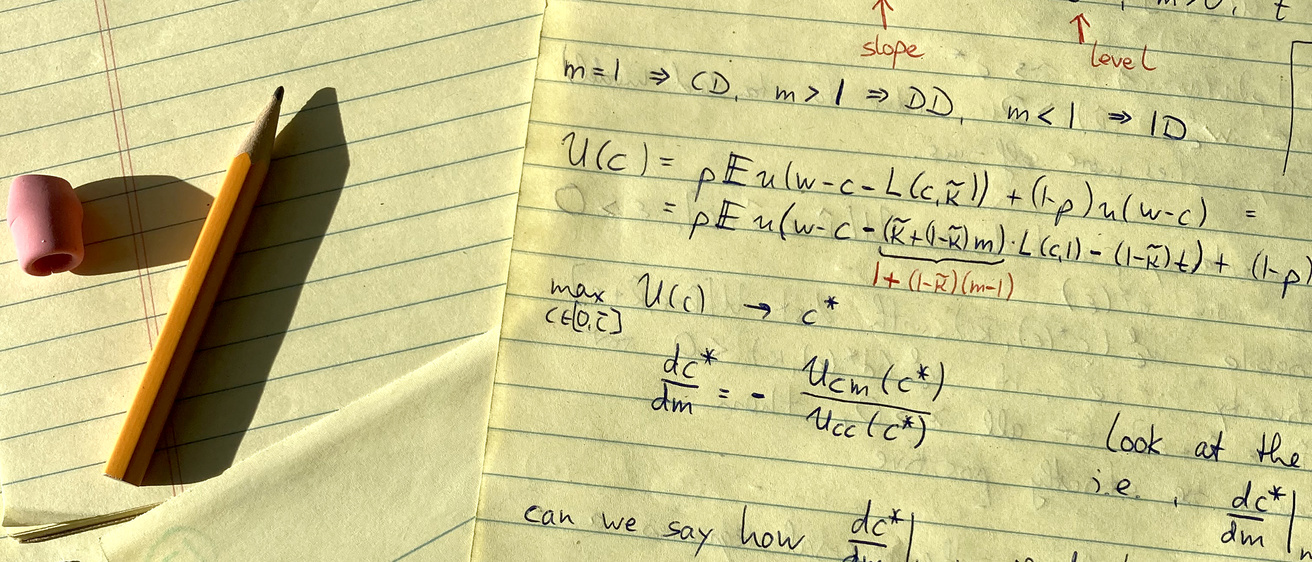

Richard Peter writes his theoretical models by hand. Sheet after sheet of symbols and signs that may leave you scratching your head.

For the untrained eye, looking at his step-by-step derivations may raise lots of questions, but for the Department of Finance’s award-winning researcher, they answer questions.

Peter came to the Tippie College of Business from Germany in 2015. He is an associate professor of finance, TriStar Fellow, and recipient of the Cannon Teaching Scholarship for Teaching Excellence. He was also chosen as the Early Career Faculty Research Award winner at Tippie in 2020.

His scholarly intelligence is only rivaled by his social aptitude. He is well liked in the college and brightens every hallway with his boisterous laugh. If this isn’t enough to convince you he’s a great guy, his research is meant to help you—the consumer—make better insurance decisions.

His applied theory research all starts with asking descriptive, predictive, or normative questions.

Descriptive questions look at data about behaviors and ask: How can we explain that?

“I write a theory that provides a possible explanation for the behavior,” he says. “If it’s a behavior that isn’t in the best interest of the consumer, then I look at how we can help people make better choices.”

In one research paper, he asks why people have such a hard time adopting preventative behaviors, like going to the gym more.

“The story we tell in that paper is that people have a skewed perception of the benefits because the benefits are uncertain,” he says. “Our argument reinforces other explanations like procrastination, but our point is if you underappreciate or don’t realize the full benefit, you’re less likely to engage in the preventative behavior.”

→ (Why you can’t keep your New Year’s resolution)

Predictive questions are used for hypothesis development. In research soon to be published in the interdisciplinary journal PLOS ONE, Peter and his co-authors look at how much effort people exert to try and avoid bad situations.

He predicted that if people know they’re going to get bailed out (for example, if people were to get 100% of their salary for unemployment benefits) they don’t have very much incentive to make an effort, especially if the money comes from an abstract entity like the government or an insurance company.

“We found evidence in the data that suggests if support comes from another individual person, ‘free ride’ behavior” is seen much less often,” Peter says. “Almost nobody wants to be the ‘bad guy’ who shirks responsibilities and takes advantage of people, so they work hard.”

→ (Guilt is real)

Normative questions ask how things should be organized or regulated. An example of this in Peter’s research is whether life insurance companies should be allowed to ask for genetic test information—like the BRC1 and BRC2 genetic mutations that can be a harbinger for breast or ovarian cancer (and the reason why many women, including actress Angelina Jolie, have opted for preemptive radical mastectomies).

→ (The "Angelina Jolie effect")

These questions quickly enter the realm of ethics and policy. Should insurance applicants have to divulge test results? What if that means they are denied life or long-term care insurance? Where do we, as a society, draw the line?

“With this issue, I think we should be very careful,” Peter says. “Insurers do need to have access to relevant information for underwriting purposes, but we should not go so far as to make it impossible for those who need the insurance. Because of what I’ve seen in my research, as of right now, I think the right approach is for insurers not to use genetic information for the sake of the consumer—and it wouldn’t be much to their detriment.”

The opposite might further erode consumer trust in insurance and make them skeptical to buy adequate coverage, which would bring us back to a descriptive question; Why are people under-insuring themselves?

If you need Peter, he’ll be at his desk, scribbling towards the answer.

This story appeared in the 2021 issue of Exchange magazine.

Iowa Connection: In his research, Peter sometimes uses an old philosophical idea about risk and probability called "Knightian uncertainty," which was named after Frank Knight, a professor at Iowa from 1919-1927. "If you flip a coin, it's a 50/50 chance, but when probabilities are fuzzy or unknown because of a lack of data, researchers refer to it as 'Knightian uncertainty.'"